Designing Peace Corps Service in Nyondo, Namibia

This case is not a traditional research project in academia or industry. However, the ethnographic mindset I practiced over the course of my 27 months as a Peace Corps Volunteer has been fundamental to my development as a researcher, so I am highlighting those foundational practices here.

Research Overview

The United States Peace Corps has three goals: 1) to provide skilled volunteers where they are requested, 2) to share with volunteers’ host communities elements of American culture, and 3) to share with Americans elements of the cultures of the host communities. Peace Corps focuses on people-to-people capacity building for community development. Service is structured to enable volunteers to immerse themselves in their communities to enable sustainable development by learning and supporting community-driven priorities.

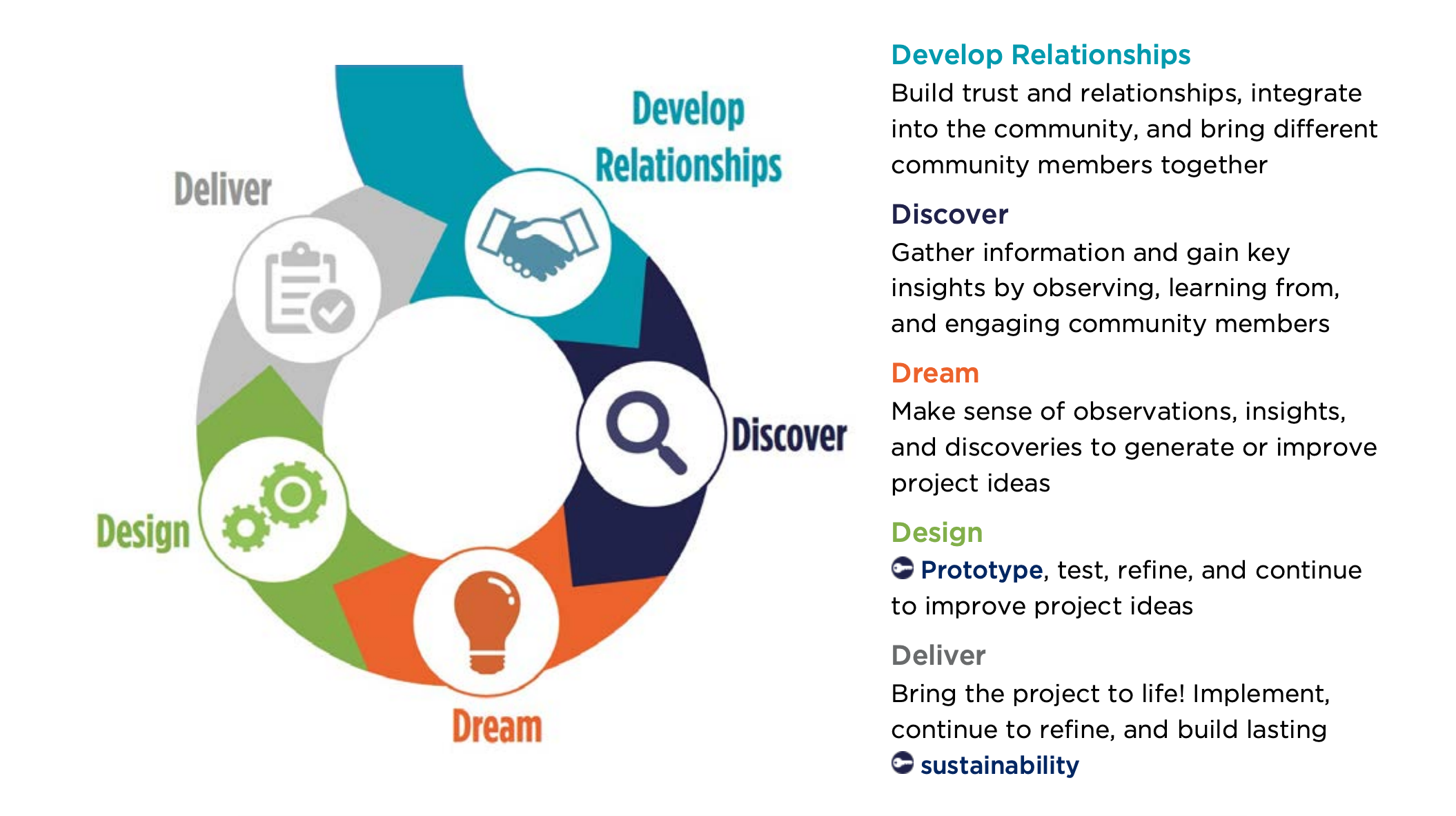

As a Peace Corps Volunteer in Namibia, I was trained and evaluated based on the implementation of a human-centered design approach to my service—primarily through the Participatory Analysis for Community Action framework.

Peace Corps Participatory Analysis for Community Action Phases. Source: The Participatory Analysis for Community Action (PACA) Field Guide for Volunteers.

TiMeline

July 2013-October 2015

Methods

My goal as a Peace Corps volunteer was to integrate into my community as much as possible in order to invest my time in priorities that were community-driven. My research was informal, but my ethnographic mindset was consistent—for over two years, I was observing and asking questions to inform my own adaptation to community norms and to design development initiatives.

Literature Review | In addition to Peace Corps formalized training on community development best practices, I pulled from my undergraduate education and ongoing research during my service to inform my analysis of development challenges on the ground.

Field Study

Participant Observation | Participant observation is the foundation of Peace Corps, from living in a similar style of accommodation to joining the staff of an institution. Formally I was a full-time staff member of Nyondo Combined School, but my scope extended beyond the curriculum of my classes to learning the culture and power dynamics of my community.

Unstructured Interviews | From my students’ daily English writing reflection prompts to conversations in the staff room to chatting with drivers on long rides hitchhiking (a normative form of transportation in Namibia) around the country, asking questions and gently probing responses was critical to building an understanding of my community.

Findings

Identifying local needs, priorities, and willingness to collaborate in moving forward initiatives informed how I spent my limited time in Nyondo. There was no shortage of opportunities and requests to which to dedicate my time. My understanding of the community’s priorities and power dynamics informed not only how I approached my work but perhaps more critically what I chose not to do. The following are select examples of how my immersive research informed the design of my services:

Government Advocacy for Basic Needs > than External Funding

The water tap at Nyondo Combined School. Although polluted, still a luxury relative to most of the village which relied on hazaradous river water.

Running, potable community water taps emerged as a leading issue. Previous water resources interventions in the region demonstrated that external funding often resulted in defunct water sources that could not be maintained while successful, sustainable sources required the support of the government, primarily the Department for Rural Water and Sanitation Coordination. Through participating in a community development committee, I partnered with community leaders to coordinate petitioning the appropriate government agencies, offering my assistance in crafting requests and organizing persistent efforts to advocate for them.

Leveraging Existing Resources for Improving School Finances

Digital Financial Management | While school financial resources were constrained, it became clear that there was also an opportunity for improvement in managing the resources the school had. One school computer and a secretary engaged with it offered an opportunity for easing the issues with the school’s financial tracking. The secretary was eager to shift to digital, and I developed a spreadsheet template for tracking the school revenue and expenses and trained the secretary in how to use it.

Photo Fundraiser | The school needed more funding, but community members did not have the resources to contribute large sums. Photos were popular locally, but most only had access to low-quality phone cameras, if that, and no access to printing images. After negotiating a discount with a photo printing shop in the closest town and determining pricing in consultation with community members, we kicked off a school photo sale that was affordable enough for community members to access and broadly popular enough to generate meaningful income through many small contributions. While the sale first relied on my personal digital camera, the effort generated enough revenue for the school to purchase a digital camera within a few months, so the work could continue independently. As important, parents and students cherished their photos.

Feature on the Nyondo Combined School newspaper partnership in The Namibian, the national newspaper.

Localizing Language Learning Content

The reading materials available at the school were largely set in contexts to which my students, most of whom had never left the village, could not relate. Over the two years of generating lesson content as an English teacher, I evolved the substance of the content based on student engagement and comprehension, including developing a partnership with the national newspaper to have old bound newspapers donated to the school library for reading content to which students could connect—they were by far the most popular reading resources in the library.

Reflection

As I have developed a more rigorous foundation in research methods through my work and graduate studies, I see where those approaches could have benefited how I approached learning my community, evaluating my work, and iterating on it as a Peace Corps Volunteer. However, as I have applied research methods, I have also found that the practice I had as a Peace Corps Volunteer in asking questions, countering my assumptions and biases, and drawing actionable insights from qualitative data are foundational to my mindset and soft skills as a researcher.